M+E Connections

Back to the Cinema?

Story Highlights

Nineteen-year-old UCLA law student Alan Shimp examines the post-COVID-19 plight of movie theaters, and what it’ll take for them to get the youngest generation of paying movie fans back in the seats.

By Alan Shimp –

In the summer of 1975, we questioned whether people would go back to the beach after watching “Jaws.” Today, we question if people will go back to the movies after the COVID-19 pandemic. The tables have turned. Instead of the film industry scaring audiences, the audiences are scaring the industry.

And if people don’t return to the cinema, the impact could be devastating.

There’s no perfect way to handicap whether audiences will return. A consulting company could crunch the numbers, but that takes time. Wall Street prognosticators or industry insiders may have some insight, but they have biases by virtue of their positions.

However, as an 18- to 25-year-old movie fan, I can provide an admittedly anecdotal sense of what the most lucrative target audience is thinking.

I believe audiences will return to the theaters. It’s human nature to get together and share stories. People have gathered around a “flickering light” for storytelling since the beginning of time. What began in caveman times evolved to cinemas by 1905. Going to a theater, indulging in highly priced concessions, and settling into the dark to share a story with a group of strangers is a ritual for which streaming cannot entirely substitute. So yes, we’ll still go to the theater.

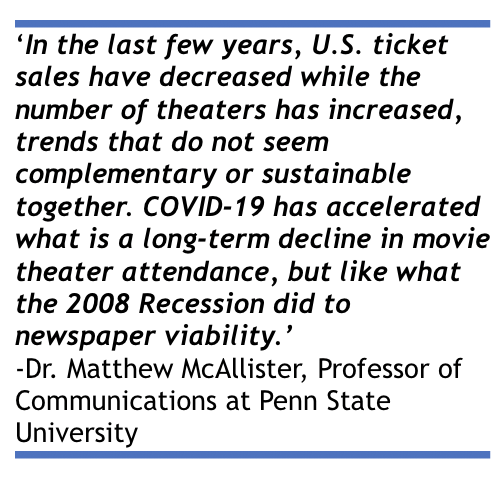

However, that doesn’t mean movie-going won’t change significantly in the coming years.

A remarkable inflection point

This is no surprise. COVID-19 and the introduction of streaming platforms have combined to create a remarkable inflection point in cinema history, but it’s not without precedent. Nickelodeons, vaudeville houses, sound, movie palaces, the Paramount Decrees, small-town cinemas with big screens, drive-ins, multiplexes, digital cinema, and much more have marked a tumultuous progression that has led to the modern status quo.

It’s also worth noting that the cinema experience isn’t the same everywhere. The experience at an upscale urban theater with reclining seats, attentive waiters, hot pepper calamari fritti, and a glass of wine is significantly different from a suburban cinema with broken seats, down-trodden employees behind the concession counter, stale popcorn, and a 42-ounce soda.

While prices range from $7 for a bargain matinee to $25 at that upscale theater, the average price for a ticket is $9.16. Adjusted for inflation, that price hasn’t increased since 1965.

On the other hand, everything else has changed and perhaps that price should have changed with it. Bell bottom jeans cost about $5 in 1965, but I wouldn’t give you anything for them today. It’s not the price, it’s the price value. So, is the movie theater experience worth $9.11 to the average 18- to 24-year-old?

On the other hand, everything else has changed and perhaps that price should have changed with it. Bell bottom jeans cost about $5 in 1965, but I wouldn’t give you anything for them today. It’s not the price, it’s the price value. So, is the movie theater experience worth $9.11 to the average 18- to 24-year-old?

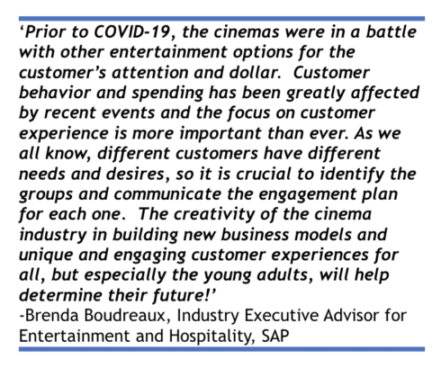

It really comes down to hours, eyeballs, and alternatives. There are only 24 hours in a day and a finite number of eyeballs that can see a movie, but there’s also a lot more competition for a viewer’s attention than there was 55 years ago. Greater competition should theoretically drive either a decrease in price or an improvement in customer experience.

Considering most young adults have been scrambling for jobs in this COVID-19 crisis, and they have student loans to deal with, that $9.11 movie ticket ($18.22 with a date) — plus the inevitable popcorn, drink, and box of Sno-Caps — looks more and more like a luxury. Given that many major motion picture budgets top $100 million, and the theaters are getting a smaller and smaller cut of the box office, I don’t see the prices coming down any time soon.

In fact, given the delays caused by the virus, prices could go up. If a film opening is delayed by six months, someone has to pay the interest on that $100 million. Syllogistically, cinemas must improve the customer experience to bring audiences back.

What this generation wants

So what kind of experience does an 18- to 24-year-old movie fan want? Well, we don’t really need the reclining seats and calamari; that’s not going to play in Peoria. I’m sure there are people in Beverly Hills that love it, but when most people want calamari, they get it from a seafood restaurant, and all they expect from a movie theater is a big screen and a bucket of popcorn.

It’s no secret that the $7.99 bucket of popcorn only costs about $0.90, and that’s just fine. It’s a traditional part of the experience and theaters rely on it to stay profitable. My generation might grumble, but at least those of us who are more informed think of it as a charity that keeps our friendly neighborhood cinema in business. However, if theaters try to raise that price or offer an inferior product, we might feel betrayed, and that won’t improve the customer experience.

After all, staying home to stream movies provides an intriguing alternative. Not having to plan our days around showtimes is certainly a bonus. We don’t have to calculate how long it will take to get to the theater or guess how early we have to be there for a good seat. Microwave popcorn and soda costs about $2, including taxes. No one is kicking the seat or talking on a cell phone, there are no screaming children, and we can pause the film for a bio break.

After all, staying home to stream movies provides an intriguing alternative. Not having to plan our days around showtimes is certainly a bonus. We don’t have to calculate how long it will take to get to the theater or guess how early we have to be there for a good seat. Microwave popcorn and soda costs about $2, including taxes. No one is kicking the seat or talking on a cell phone, there are no screaming children, and we can pause the film for a bio break.

We can re-watch scenes we missed, adjust the volume, switch to different content if what we’re watching doesn’t appeal to us, and multitask on our own phones without upsetting anyone else.

One of the biggest myths about the cinema experience is the advantage of a big screen. Forget about that. Yes, in the Dark Ages, the theater experience was much better than a VHS tape shown on a CRT television, but my family has a high-def TV with surround sound now. When I’m in my own apartment, even my laptop works just fine. If I want a bigger screen, I can sit closer. On the other hand, if I go to a crowded blockbuster film at the cinema, I may find myself in the first row on the end, watching the film at some neck-wrenching oblique angle. Even THX sound isn’t going to be optimized for that seat.

Ticket price is a more interesting factor. The home viewing option requires internet service, but most of us already have that. Subscription or transaction fees are generally less expensive than the ticket price, especially for people who consume a lot of content. COVID-19 is driving a lot of demand for AVOD as well, something particularly notable in light of its impact on the income of Gen Z.

Of course, a key motivation behind movie-going is hormones, the driving force behind the behavior of most 18- to 24-year-olds. It’s not a coincidence that going to the theater with someone special is a traditional date-night outing. While passions are frequently enflamed in a dark room, the safety of a public place and the absence of awkward conversation make it an ideal way to get closer without getting too close. It’s also a shared experience. Having watched a film together, a couple will have gone on a sort of journey with each other.

They reach a sense of mutual satisfaction and bask in the afterglow of catharsis without one button coming undone. On the other hand, going back to an apartment to stream content, conversely, is a high-risk proposition. It’s likely more “chill” than “Netflix” and thus an entirely different subject.

Problems (and hopes) ahead

I’m looking forward to going back to the theater. I’d love to sit in a packed house watching the premiere of a newly released blockbuster. (I’ll be there when “Wonder Woman 1984” finally opens). It’s great fun when the audience collectively holds its breath watching an action film, laughs at a comedy, or screams at a horror film. But I don’t think that’s going to happen if I’m six feet away from the next person in all directions and the hot air escaping from the top of my mask is fogging my glasses.

As the present conflict between Universal and AMC Theaters shows, this will be a major problem for distributors and cinemas. They depend on a big opening weekend to create a buzz and turn a profit.

As the present conflict between Universal and AMC Theaters shows, this will be a major problem for distributors and cinemas. They depend on a big opening weekend to create a buzz and turn a profit.

There will be a lot of competition to fill screens in the last quarter of the year, but each auditorium will only be able to fill to one-third capacity. Somehow, they’ll have to make it work, especially since there are pre-existing contractual obligations on the line and delays will create complex disputes further exacerbated by closed courts. Susan Kay Leader and Josh A. Rubin of Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Field give a good breakdown of some of the logistical issues caused by the shutdown for the entertainment industry here.

I might be up for a midnight movie, but if they start raising the price of the popcorn or cutting some other corners, I might be more inclined to stream. And if they don’t raise the price of the popcorn, how are they going to pay the concession guy to work the midnight show? How can they even run the usual daytime shows on one-third the revenue?

The central focus of the media and entertainment industry is to create a great customer experience. As the world changes, so do the expectations of customers, and the need to innovate a better experience becomes critical. Audiences want to return, but that won’t be possible unless cinemas innovate to cost-effectively surmount these exogenous challenges.

No one has ever saved their way to prosperity and cinemas will not become more profitable by giving their customers a worse experience.

Alan Shimp is a 19-year-old, third-year law student at UCLA earning a certificate in entertainment law, who would love nothing more than to work in business and legal affairs in the media and entertainment industry. He’s co-author of “The Film Fan Handbook” series. Connect with him on LinkedIn.