Exclusives

M&E Journal: A Cloud-Based Digital Supply Chain: Not Just About Capacity

Story Highlights

Andy Shenkler, Sony DADC New Media Solutions –

The list of options in today’s world is seemingly endless with tools such as social sharing, instantaneous commenting, photo filters, unique storytelling, augmented reality, virtual reality, 3D, 4K, 8K, HDR, 7.1, 9.1, and 12.1. With access to so many opportunities, the barrier for creating a unique proposition is lower than ever, allowing almost any company to create niche offerings and to attract a consumer’s attention. The hardest part, of course, is getting the consumers to know about it, try it, and, most importantly, adopt it for the long run.

In the world of Hollywood mashup stories, everyone wants to be able to tell the easy elevator pitch, like Die Hard meets Airplane. Unfortunately, people believe that it is too difficult to make content readily available for all these progressive experiences. This has been especially challenging when the content is needed in any variety of combinations that would lend itself to be used in these untried methods. Too often, it can become so overwhelming that it may make one seek a simplified mechanism to distribute all of the required content to everyone who wants to use it.

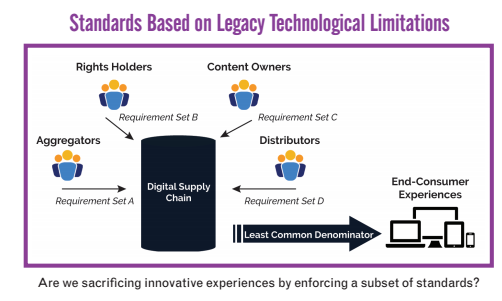

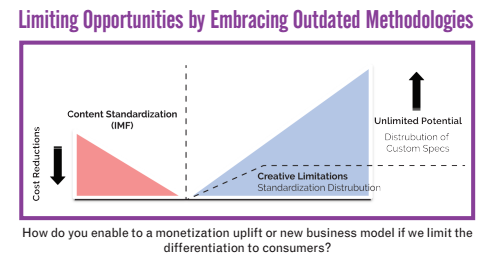

Determining the value of standardization- Standardization on the backend can be beneficial, but does it really foster the right amount of innovation and competitive spirit? Often times, not conforming to standards is required to deliver something so uniquely valuable that we, as consumers of content, don’t miss out. There is a view that seems to be taking hold across the industry that end-to-end standards need to be mandated in order to reduce complexity and make things more predictable. Effectively, these viewpoints express that the supply chain provides no differentiation to the consumer service, but rather that the user experience and content alone should provide that point of differentiation.

That view is often articulated by existing market leaders who require the supply chain to provide content in a way that is most efficient for one particular set of needs. What if there is a need to provide an experience that is meant to try and disrupt that market leader? How could that possibly be done if the supply chain was made to fulfill the least common denominator, especially if the requirements that were used were driven by the exact organizations one was looking to compete with or disrupt?

The same question should be addressed from rights holders, who, for all intents and purposes, are looking to cost effectively get their content in front of as many people as possible.

The media industry has the benefit of being among the first industries to push the limits of technology for the masses and watch in real-time as people respond. At times, it would appear as if consumption desires are at conflict with our backend strategies.

Over the last twenty years, there have been numerous incarnations of digital distribution systems imagined, realized, torn-down, reimagined and built again. As with all things, one’s understanding of how we arrived at where we are today has much to do with one’s own perspectives, and how one got involved in the first place.

It’s certainly not to say that the individuals who started building early solutions didn’t have a clear vision of the ideal end state.

Most of the time, it was the age-old problem of limitations, such as money, time, and technology, that interfered; fortunately, inadequate technology is no longer a problem that which we face.

Most of the time, it was the age-old problem of limitations, such as money, time, and technology, that interfered; fortunately, inadequate technology is no longer a problem that which we face.

Some of the earlier digital deliverables for broadcasters were in the form of MPEG-TS formats, often 80Mb/s for HD and 50Mb/s for SD. Since MPEG was the most prevalent asset type requested, many companies spent small fortunes encoding their content in this format because it would make it easily available for reuse. This would then become their highest digital source asset.

The idea of storing an uncompressed source, or a source of any higher quality from which to create these assets, was obviously considered, but storage costs were high and transcoding was slow. When the measure of success was “-it’s faster and cheaper to ship a tape,” you make compromises that allow you to move a transformative initiative forward.

Fast forward slightly to iTunes requiring all content owners to provide their video components in the Apple ProRes format. At first, this was met with resistance from some due to the fact that they would need to start over and re-encode, from tape source, their content. Over time, the format conversion eventually won out, and catalogs started to be re-encoded making ProRes another, yet again higher, resolution video source component.

The next format that started to make headway around this same time was JPEG 2000 (J2K), which has been adopted by SMPTE as the basis for the App 2 and 2e versions of the Interoperable Media Format (IMF).

The IMF is meant to be the long sought after “be-all, endall” to allow all versions of content to exist in a single definable package, by which any edit of media can be derived. Once again, many companies are undertaking this encoding exercise to store their assets in what they hope will be the final incarnation of an expensive effort they have done so many times before.

Seeking consistency in components, workflows

As we moved forward towards present day, video tended to be the components that were most discussed since they held the core value to consumers. However, for everyone involved, it quickly became clear that ancillary components, artwork, text, audio tracks, and metadata were an even bigger problem in most cases. To this day, there are still companies that will deliver video independently from the other assets that are required to complete a transaction. Often times an organization will require the recipients to go to a portal to download artwork, or will send an Excel file with title avails information, and possibly will even send an email with attachments. Anyone who thinks only the video aspect of this process is complicated doesn’t understand the half of it.

It’s no wonder that so many called for a streamlined, predictable and standardized workflow to be implemented. A single definable package of information that can be used to exchange rules, descriptions, content types, or anything else that is required as necessary. It all seemed like a great idea, especially when everything was costly, slow and complicated.

As we reach a point in time where delivering on that goal of standardization is so close, we now have the benefit of seemingly infinite capacity on demand at incredible commoditized pricing. Yes – cloud computing.

Since digital distribution first came on the scene, everyone has either seen or used a variation of the slogan, “any format, anytime, any place.” So if that is truly the ultimate goal, then how does delivering the same thing to every company, in the same format, achieve that ideal end state?

There is no question that standardization of source components is a critical undertaking that content owners should address. The IMF format begins to address a significant piece of that puzzle. The aspects of augmented and virtual reality will undoubtedly present new challenges that need to be contemplated for those source containers. The ancillary materials are just as important.

Every offering wants to create an experience for the consumer that makes their proposition unique; whether it’s descriptive information that exists only on their destination, or artwork that takes its shape, not from the traditional square/rectangle but from a creative design.

Every offering wants to create an experience for the consumer that makes their proposition unique; whether it’s descriptive information that exists only on their destination, or artwork that takes its shape, not from the traditional square/rectangle but from a creative design.

Imagine an augmented reality experience whereby the consumer looks out amongst the world only to see objects from their favorite movie or TV show appear before them, which then end up being selectable components to add to inventory or to choose to preview other video experiences.

With the recent success of Pokémon Go, that’s certainly not as impractical as perhaps many thought.

As standards like the Entertainment Merchant Association (EMA) spec are driving supply chains to deliver a common set of components in a common set of formats, it requires that everyone adopt a particular set of ways of accepting those elements.

At the speed that innovation is progressing, it seems undesirable that we should either want or require this level of conformity when the ability to deliver against customized needs is now so easily accommodated through leveraging the power of the cloud.

While the aspect of a many-to-many supply chain has been seen as an obstacle in the past, that viewpoint is rapidly dissipating. You don’t have to look beyond the physical world to see the impact of how a uniquely provisioned supply chain can benefit an organization. For instance, Amazon’s physical supply chain is incredibly powerful and progressive.

The innovative way it chose to store goods by using space allocation as opposed to traditional clustering methods has proven to be unique and advantageous. Simply using the power of its supply chain has made it an innovative powerhouse, with no signs of stagnating in the near future. In much the same way, leveraging the power to create anything required for digital distribution points should only be limited around legal usage and not legacy distribution philosophies.

Building a future-proofed supply chain that allows all parties in the ecosystem to get what they need, without having to abide by rules that may have come from their competitors, is important for the growth of our industry as a whole. It’s not to say that standards such as the EMA aren’t valuable, as they should exist for those who wish to use them.

However, must they be required when the ability to cost effectively create everything from anything is now finally possible? Every day the ability to transform and deliver upon the more complex requirements becomes easier to achieve.

If your digital supply chain relies heavily on an organization that is predominantly made up of people who are taking orders and operating computers like they are heavy machinery and isn’t primarily comprised of software developers, then at some point soon, you will realize that you are nowhere close to being able to keep pace with the imagination of your customers. Thus, once again, this will force everyone to rethink their approach on supplying digital content in a world that is, fortunately, constantly evolving.

—

Click here to translate this article

Click here to download the complete .PDF version of this article

Click here to download the entire Spring 2016 M&E Journal